New CD-LINKS Research Forecasts High Emitting Countries to Suffer Economic Damages from Climate Change

Novel international study indicates actual cost of global warming will be highest for the three top emitting countries (China, India and US), and globally higher and more unequal than normally assumed. Among the authors, scientists from EIEE (European Institute on Economics and the Environment), the partnership between RFF (Resources for the Future), the energy and environmental economics think tank based in Washington DC, and member of the CD-LINKS consortium CMCC Foundation – Euro-Mediterranean Center on Climate Change. The paper is published in the latest issue of Nature Climate Change.

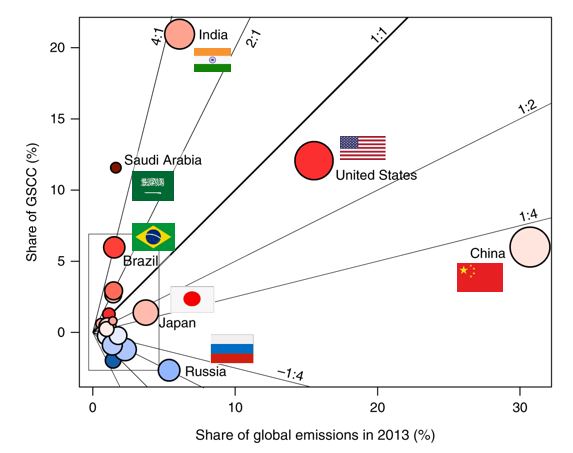

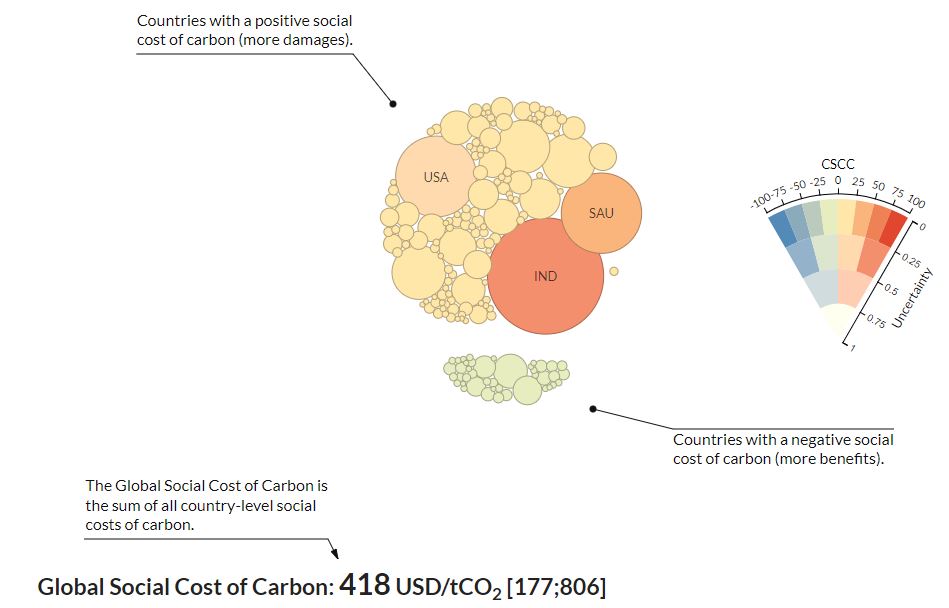

For the first time, researchers have developed a data set quantifying what the social cost of carbon—the measure of the economic harm from carbon dioxide emissions—will be for each of the globe’s nearly 200 countries, and the results are surprising. The top 3 emitting countries – India, China and the US – have the most to lose from climate change. Gulf countries like Saudia Arabia also score very high.

The findings, led by an international team of scientists and which appear in Nature Climate Change, estimate country-level contributions to the social cost of carbon (SCC) using recent climate model projections, empirical climate-driven economic damage estimations and socioeconomic forecasts. In addition to revealing that some counties are expected to suffer more than others from carbon emissions, they also show the global social cost of carbon is significantly higher than the one typically used.

Among the state-of-the-art contemporary estimates of SCC are those calculated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The latest figures range from $12 to $62 per metric ton of CO2 emitted by 2020; however the new data shows that SCC to be approximately $180–800 per ton of carbon emissions. What’s more, the country-level SCC for India, China, US and Saudia Arabia alone are estimated to be above $20 per ton – higher than the carbon prices of the European Trading System – the largest CO2 market in the world.

“We all know carbon dioxide released from burning fossil fuels affects people and ecosystems around the world, today and in the future; however these impacts are not included in market prices, creating an environmental externality whereby consumers of fossil fuel energy do not pay for and are unaware of the true costs of their consumption,” said lead author, UC San Diego assistant professor Kate Ricke. “Evaluating the economic cost associated with climate is valuable on a number of fronts, as these estimates are used to inform environmental regulation and rulemakings.”

In order to model the effects of CO2 emissions on country-level temperatures, the authors use an innovative approach by combining results from several climate and carbon cycle modelling experiments to capture the magnitude and geographic pattern of warming under different greenhouse gas emission trajectories, and the carbon-cycle and climate system response to carbon emissions.

Since carbon dioxide is a global pollutant, previous analysis has focused on the global social cost of carbon; however a country-by-country breakdown of the economic damage global warming will cause is important for various reasons.

“Our analysis demonstrates that the economic costs of climate change will be high in many countries, including ones like the US and Gulf Countries which traditionally have not taken leadership on climate policy” said Massimo Tavoni, Associate Prof. at Politecnico di Milano, Director of EIEE – European Institute on Economics and the Environment and an author of the study. “Moreover, 90% of the world countries will lose from climate, and these impacts will exacerbate global inequality and international tensions. Many countries have not yet recognised the risk posed by climate change. This study aims at filling this gap”.

The authors have harnessed the power of data science by generating hundreds of scenarios spanning socio-economic, climate, and impact uncertainties. This complex space has revealed many clear insights as well as many areas of uncertainty. “Although the ranking of world powers affected by climate change is robust across scenarios, the magnitude of the social cost of carbon is subject to considerable uncertainty” says Laurent Drouet, a senior scientist at EIEE, author of the study and developer of a visual interface which allows navigating the results (//country-level-scc.github.io/explorer/).

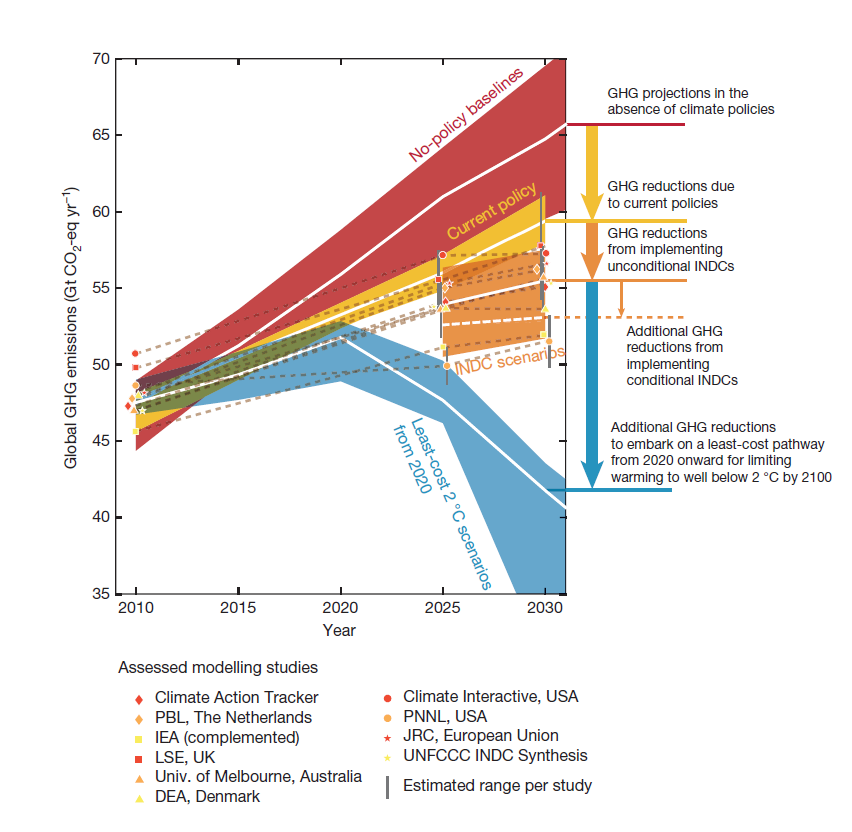

The authors noted mapping domestic impacts of climate change can help better understand the determinants of international cooperation. The nationally-determined architecture of the Paris climate agreement—and its vulnerability to changing national interests—is one important example.

Research leading to this paper has been partially supported by the European Research Council (ERC), through the project COBHAM, and the Horizon 2020 project CD-LINKS.

The text of this press release has been republished with permission from EIEE.

17 March 2016

17 March 2016